This New Book Writes About People That Not Many Others Do

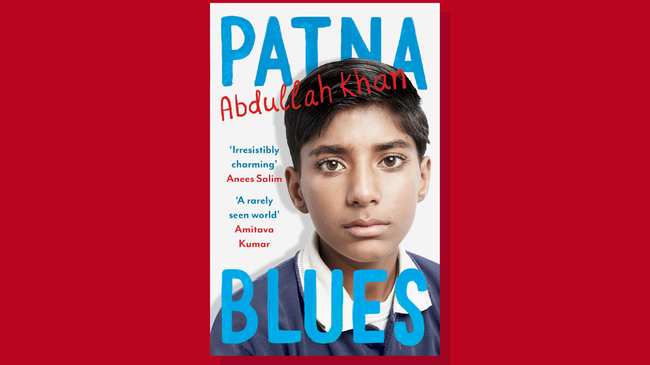

A lower middle-class Muslim boy falls in love with an older, married Hindu woman in Abdullah Khan’s debut book. We take a look at where Patna Blues intersects with the author’s life.

Abdullah Khan (47) was helping his younger brother study for his exams, when he first chanced upon a copy of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. Khan was flipping through the groundbreaking dystopian allegory when he discovered that Orwell was born in Motihari—a sleepy town and capital of Bihar’s East Champaran district—which also happened to be where Gandhi kickstarted his Champaran Satyagraha, and 50 kms from where Khan himself lived for a good part of his childhood. “Maybe that’s when I first thought of becoming a writer too,” he says. “Orwell didn’t influence my writing as much as he made me wonder if I, a country bumpkin, could be a writer too.”

Earlier this month, Khan came out with his debut novel: Patna Blues set in the 1990s, drawing to some degree from Khan’s own background, culture and life. To know where the narratives intersected and where they diverged, we got on a call with Khan.

Fiction: Khan’s novel is many things at once. You could read it as a simple, sweet yet heartbreaking coming-of-age story of a lower middle-class Muslim boy based in small-town India—a setting not abundantly found in Indian writing in English.

Reality: Khan grew up in a sleepy little village called Pandari. He was educated for most of his school years in madrasas or Islamic seminaries, as also Hindi- and Urdu-medium school. He moved to Patna when he was in Class XII. “When I landed in Patna, it was a mythical city for me,” he says. “The best thing about it was the continuous supply of electricity that allowed me to study, and running water.”

Reality: Khan grew up in a sleepy little village called Pandari. He was educated for most of his school years in madrasas or Islamic seminaries, as also Hindi- and Urdu-medium school. He moved to Patna when he was in Class XII. “When I landed in Patna, it was a mythical city for me,” he says. “The best thing about it was the continuous supply of electricity that allowed me to study, and running water.”

Fiction: Khan’s story could also be a narrative of what it means to be a Muslim in a post-Babri era. When his protagonist, Arif, falls in love with a married Hindu woman who is also older than him, his primary anxiety is not to do with unrequited love but how its exposé would shame his family. When he fails an exam, he wonders if he’s not been passed because he is a Muslim, while rioting mobs make a couple of appearances through the book too.

Reality: “When I moved from Bihar to a town in Uttar Pradesh and then other places, I would be asked ridiculous questions like whether my father had married four times. When I then moved to Mumbai, I had to move around for almost 10 days to look for a house. Some would tell me straight-up that they were not comfortable with me renting a place because I am a Muslim, whereas some would make up some excuse. Once, when I was passing through Ayodhya for work, there was a big conference of Bajrang Dal or VHP members, and some of them had closed around our bus. I was immediately scared about what would happen if they asked my name. Thankfully, they didn’t.”

Reality: “When I moved from Bihar to a town in Uttar Pradesh and then other places, I would be asked ridiculous questions like whether my father had married four times. When I then moved to Mumbai, I had to move around for almost 10 days to look for a house. Some would tell me straight-up that they were not comfortable with me renting a place because I am a Muslim, whereas some would make up some excuse. Once, when I was passing through Ayodhya for work, there was a big conference of Bajrang Dal or VHP members, and some of them had closed around our bus. I was immediately scared about what would happen if they asked my name. Thankfully, they didn’t.”

Fiction: Almost at the very start, you come across Arif penning some lines in Urdu poetry as an impulsive response to seeing a beautiful woman. You find Urdu couplets in the inner pages too, reminding you of Arif’s background and cultural reference points.

Reality: A madrasa education with Urdu as the primary language means Khan is well-versed in the language even though he “can’t dare write in the language in which so many talented people write”. When in college, Khan used to write poetry but what inspired him to go long-form was Arundhati Roy’s Booker Prize win for The God of Small Things. “The day her inspiring interview was published in a magazine was the day I started writing.”

Reality: A madrasa education with Urdu as the primary language means Khan is well-versed in the language even though he “can’t dare write in the language in which so many talented people write”. When in college, Khan used to write poetry but what inspired him to go long-form was Arundhati Roy’s Booker Prize win for The God of Small Things. “The day her inspiring interview was published in a magazine was the day I started writing.”

Fiction: Arif’s father is shown as a morally upright sub-inspector who dreams about his son being an IAS officer.

Reality: Art mimics life here, with Khan’s father also being an inspector with the Bihar Military Police. “He was as non-corrupt, and though he wanted me to take up IAS too, I wanted to pursue media studies." Bihar was, for the longest time, an IAS-producing factory, churning out an impressive number of candidates. "I gave the preliminary exam for it too but thankfully, didn’t clear it. And when I accidentally got an opportunity to work with a bank, I took it up.” Khan now lives in Mumbai with his wife and two daughters, and is Assistant Vice President at Axis Bank.

Reality: Art mimics life here, with Khan’s father also being an inspector with the Bihar Military Police. “He was as non-corrupt, and though he wanted me to take up IAS too, I wanted to pursue media studies." Bihar was, for the longest time, an IAS-producing factory, churning out an impressive number of candidates. "I gave the preliminary exam for it too but thankfully, didn’t clear it. And when I accidentally got an opportunity to work with a bank, I took it up.” Khan now lives in Mumbai with his wife and two daughters, and is Assistant Vice President at Axis Bank.

Fiction: The book is heartbreaking in ways more than one. The struggles to achieve what they set out for are big elements in the lives of Arif as also his brother who everyone thought was destined to be a famous actor.

Reality: Khan’s writing career took a long hiatus during which he got a job with a bank, and got married. It was his wife who then discovered his dream of writing a book and pushed him to realise it. “She almost blackmailed me,” he laughs. “She would step out of home on Sundays and ask me to write all day in peace.” Khan finished the book in 2009, but it would still take him nine more years and 200-plus rejection letters from publishers and literary agents before seeing it published and out in the world.

Reality: Khan’s writing career took a long hiatus during which he got a job with a bank, and got married. It was his wife who then discovered his dream of writing a book and pushed him to realise it. “She almost blackmailed me,” he laughs. “She would step out of home on Sundays and ask me to write all day in peace.” Khan finished the book in 2009, but it would still take him nine more years and 200-plus rejection letters from publishers and literary agents before seeing it published and out in the world.

Fiction: In Patna Blues, political and sociological undertones are everywhere, from ‘love jihad’ to what struggling actors who come to Mumbai go through—though never in a way that they overwhelm you. But more than anything, it all just feels real even though the reality of the reader might be vastly different from that of our hero’s.

Reality: Khan is now working on his second novel—Aslam, Orwell and a Porn Star—that talks about a guy who’s born in the same house as Orwell, and begins to think he is an incarnation of Orwell himself. “This will be a purely political novel. Most Indian writers writing in English try to incorporate NRI experiences. Which is why you rarely find people like me—those from a rural background and coming from lower middle-class families and marginalised—writing in English. But the stories of these invisible people need to be told too.”

Reality: Khan is now working on his second novel—Aslam, Orwell and a Porn Star—that talks about a guy who’s born in the same house as Orwell, and begins to think he is an incarnation of Orwell himself. “This will be a purely political novel. Most Indian writers writing in English try to incorporate NRI experiences. Which is why you rarely find people like me—those from a rural background and coming from lower middle-class families and marginalised—writing in English. But the stories of these invisible people need to be told too.”

Patna Blues is published by Juggernaut (Rs 499)